An Interview With a Maintainer: Vincent Lai

SUMMARY KEYWORDS

repair, fix, maintenance, laptop, lamps, broken, hard drive, screens, repair shop

On October 13, 2023, Lauren interviewed Vincent Lai, a longtime Fixer Collective leader for the past decade and a dedicated member of the maintenance and repair community. In this conversation, Vincent reflected on the value of community-building and self-sufficiency through fixing, and also, how being able to repair your belongings can bring purpose and a more meaningful level of ownership towards the everyday objects we use. Vincent is based in New York City, and organizes pop-up repair communities that are free and open to the public every Thursday- follow them on and join the next one!

In order to make the interview conversation more readable, it has been edited and adjusted. On request, a transcript of the interview can be provided.

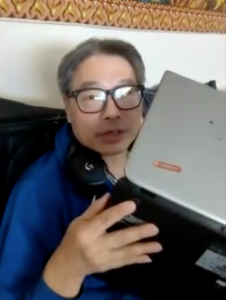

Caption: Vincent Lai, part of Fixer Collective, shows us the “I fixed it” sticker on the laptop he fixed.

Lauren : Can tell us a little bit about your background, and how you came to be a maintainer, or someone who dedicates a lot of time to repair, and maintenance?

Vincent: A lot of my background came from what other people may describe as folk methodology, just getting together on a very casual and informal basis, to tinker, to get hands on, and to just dive into things to see how they work, how they don’t work, and if they’re broken, how to fix it. That evolved into me finding other people, finding the groups. Most of them were informal up until about 2010, when I discovered the “Fixers Collective”. I’m not the group founder, but I joined up with it shortly after it was created. And since then, we’ve been holding regular meetings to skillshare. We’ve been doing it since 2010 and until 2020, and resumed shortly thereafter. So a lot of my training and background came in formally. Nothing came from the academic side, if you will. That’s pretty much how I got started. And we’re still holding workshops, performing community outreach, and showing people how to get their things fixed up.

L: That’s great! So is that 10 years then, that you’ve been part of the community?

V: Yeah, about 10 years or so. I mean, there’s been a little bit of that beforehand, on a very informal basis. And part of the things where I was inspired and motivated to continue fixing and repair actually came from the demise of a bunch of dot.com companies. When the bubble burst, they had to get rid of this stuff! So I was there, at their liquidation sales. I would find a laptop or two… one of them just had the cosmetics, I bought it for $100, I got cosmetic parts for 20 and whipped it out and sold it on Craigslist 400… I was very, very happy about that. Another challenge came when I got another laptop with a busted screen. So I’ve never done that before. I got the part, figured out what I need to do. A lot of it was my own backend, because the instructional videos that I would see on YouTube, and the iFixIt guides weren’t there at that time. I do actually remember stripping a screw so I had to figure out how to get it out. I was able to do that and this was my daily routine for a few years up until I moved on to other parts. So a lot of that again, informal happenstance, fortuitous random stuff, that’s the path I took and that led me up to here.

L: And was that connected to your professional background or was it more like a hobby?

V: It was more like a hobby. Back then, I was doing more management consulting work, but you know, it was very hands off, in a way black box, because it wasn’t sure how things worked inside, as opposed to even something like an iPad or a laptop has a black box type process where you can’t really see electrical signals and impulses going through the machine. That’s why we really like mechanical challenges, because the feedback is instant. It’s very visible, and we can act quickly on it.

L: It’s so interesting how you’ve been doing this as a hobby and that you’ve kind of gained this experience that is very self taught or that you’ve kind of done a lot of that on your own.

V: Some of it was self taught. A lot of times, they’re just asked by my friends or the community, like “Can I fix it? How do I get it done?… You know, I got an iPod button with a mushy button.. how do I fix that?” And I’ll get responses and work on that. Sometimes I’ll contribute, somebody will ask, “Yeah, my kid threw the Wii controller at the TV and it’s cracked, what can I do?” And that’s actually one of the few times when I would type in say “Not much! The glass panel can’t be fixed, at least I’m not aware of it. And replacing the glass cost a lot more than replacing the TV.” So I’ll chime in with other other things and techniques that I’ve learned along the way, too.

L: How does that skillshare happen? Is it when you all have the meetups in person? Or is it virtually that people kind of pose a question on a virtual forum, and then you all give your knowledge of whether it can be fixed or not?

V: Just about all them or on a pop up basis, in person. We have them on the third Wednesday of every month, at Hack Manhattan in Midtown. We will get together for a few hours. And we all take a look at what people brought in, give our thoughts and then implement the repair. Ideally, we want to pull people in and have them participate. Because we want to get away from the classic model where people would just drop their stuff off and have all of us work on it. It also helps us divide the labor a little bit more evenly. On a really, really busy day, sometimes people have to wait. We have a policy where if somebody really, really insists that they just drop it off, we kind of manage their expectation by saying, “Well, we’re going to work on the things that other people have brought in and will stay to fix”. So other people get put in the back of the line. And that may mean that we may not work at all that night. Just about all of our meetings are physical face to face meetings, although we try to participate in other virtual meetings. Fixit Clinic has them very often, on a virtual basis. So we like to come in and see what other people have. They’ll have their green screen, and they’ll have their item and we’ll kind of look at it and they try this, try that. But most of our gatherings happen face to face.

Caption: Two fixers repairing a fan.

V: It’s hard for me to figure out how many people are bringing face to face to drop offs in a classical model of a repair shop, partly because the shops are dwindling. We do have esteemed colleagues that are called Fix-up, run by Sandra Goldmark. She’s a Columbia University theater professor. I haven’t heard from them in a while. But one of their staff members, Adam Dowis, will be holding a lamp workshop at BIG Reuse. That’s the only time when I’ve heard of people using a classical model (dropping their stuff of)f. We get anywhere from 20 people bringing stuff in over three hours to one, you know, like in August, or July, when everybody wants to go on vacay including some of our core fixers so it varies wildly. I’ve been trying to update a little bit by just getting back with the social media presence- we’re still in a way, implementing our business continuity plan, since everything shut down in 2020. And now we’re coming back up because the routines that we had, were really, really disrupted. Simple stuff, like posting photo albums, making announcements. So we’re working on that.

L: How do you feel that you yourself contribute to repair and maintenance in your community?

V:I, I like to make an analogy, or bring up a situation. Not that I’ve done it, but we want to give people an option. Instead of having to choose between getting your laptop fixed, which is your livelihood, or maybe paying your rent. I mean, we’ve seen that where, like a Business Insider article, said, you know, Apple wanted $1,200 to fix a laptop. But a mom and pop shop did it for $200 or $300, with a part that only cost a nickel. And so we want to be able to help people get empowered, bring themselves to another level of ownership with the things that are in their lives. So that when they do break, they can at least go inside, do some diagnostic work. And then all right, if it’s beyond their pay grade, they can take it to somebody and we want to give them options too. Instead of Apple’s authorized repair centers, go to a mom and pop independent shop that may cost less. We want you to keep things out of the landfill. And also use it as an opportunity to educate and demystify some of this stuff. Some of it’s dangerous, but you can be responsible and safe when you work with stuff like electricity when you rewire a lamp. One of the things that we get the most often are lamps, and what my colleagues call heating element devices: the toaster oven, the kettle, the coffee machine. We get those just as often.

L: Do you have any idea why you get those items more often?

V: I think that the lamps, there’s a lot of sentimental value attached to them. We rarely get the lamp that came from Walmart and just broke down. Last month, we got a lamp that was originally used to run off oil and it was retro-fitted to work with electrical wires.

Caption: A group of fixers repair a lamp, the most frequently brought object.

The owner wanted to just get a refresh on the wires. The brass had a nice patina on it, and we saw the little glass oil jar, and it’s been in the family for several generations by a grandfather who either bought it or passed it down. We were able to wind wires through it, put it back together. Part of the reason why we get lamps so often is to preserve that sentimental value and to also kind of enhance that value by making it work. I mean, if it didn’t work, it’ll be all right… But I think a lot of people would much prefer that it would be functioning and provide light.

L: That’s great. It’s so interesting that that lamp trend happens, it sounds so beautiful too. I’m thinking about that point on ownership that you say, it seems that you also want to educate people to relate to their objects in a different way. It sounds like you think that through the knowledge of how to repair them, people can connect with objects differently, or more deeply.

V: I like to refer to pets as a great analogy. In the same way that you take your pet fur to the vet, you give it basic care and maintenance, and then brush your coat or trim nails or something like that, this happens to the things in our lives. You might not check a lamp cord very often. But for a laptop, you may just just want to look and see if you can tidy up the inside of the hard drive, or maybe run a little air through the ventilation to get the dust out, and maybe provide better cooling. So things like that. Provide that level of emotional investment that forces you to preserve it, if something were to happen to it. So actually, this laptop right here, you might see the little I fixed it sticker that had the old red logo on it. Somebody in my informal repair group just showed it to me and said “Can we do anything about it, it has a cracked screen?” I said, “Well, you do need a cracked screen.” He didn’t want to go through that, so because I took the time and effort to fix this, I will do other things. And actually, the hard drive did go and I took a little time to fix that up to, I hope to keep it or maybe a few more years. But when it’s done, I’m ready for the next one. To, to work on. So by making that invoke emotional investment, you want to people want to preserve it, and validate it by by just keeping that momentum going.

L: That’s great. And I love that you have a sticker for that too, to signal it!

V: You only want to put on laptops, everybody puts a lot of other decals and stickers on everything. I try to stay away from that. And that’s the one exception.

L: So how do you understand the role of maintenance and how it contributes to a more caring world? That’s the mission of the Maintainers, to take maintenance as a portal into having a more caring world. So how does that resonate with you?

V:I think maintenance is incredibly underrated. It’s pretty vital. Very few things in our lives are maintenance free, they do need some attention. And I think that making a more active effort to give more attention will bring a lot of things like. So that kind of life extension, that just gives us an opportunity to keep what we have for a lot longer. And also, you know, when it’s time to give to another owner, we can easily do that. And even at a point where you can do anything. A lot of people will take a broken item and turn it into their own project. You know, that’s how that’s how I get a hand on some of the things that I have. In terms of repair projects I remember we were hosting Maker Faire just last weekend. And I was working on a bunch of things and they just realized, man now this would be a great trifecta, because I had an Xbox 1… It had a hard drive, an AC adapter (which had bad parts in it) and also had controller parts. So I thought it’d be super cool if I were to create a completely working system out of an entire set of broken parts. So I think that maintenance is critical to getting that done.

L: Obviously, we live in a very throwaway culture, and I don’t know if it’s a generational thing or also like the practicality aspect, but it comes up in our communities’ discussions, that sometimes it’s just easier to buy something new than to put the time to repair it, especially if, if that is not your hobby, or your interest. What are your thoughts on how to educate people that don’t have that interest? Is it something that you think should be learned? Or shouldn’t they? Yeah, I’m just curious to see how you would think of engaging people that just feel that they don’t have time or interest in that.

V: I think the first thought that comes to mind is to appeal to their wallet. With a little bit of effort, you can keep your broken item working for a little bit longer. That’s why I’m thinking a very long time ago, somebody brought in a lava lamp that they bought, and it broke, but they actually had the chance to return it. But instead, they really, really want to know how it works. And so they brought it to us. I’m actually not sure if we fixed it. But we were very heartened to see that somebody had that level of interest in figuring out how stuff works.

Caption: A group of fixers take on a new challenge: fixing a lava lamp.

And I think also, that kind of speaks to the mission of trying to demystify and try to get that black box nature out and try to figure out how things work inside even, you may not see the electricity that goes on, you can just like point to little parts and just try to figure what they do. Show them a hard drive. This tells him that this is where all your good stuff is stored and you need the plastic or the metal that surrounds it. And I think that also kind of speaks to the appeal of some vintage items. Because a very long time ago, in some old time radio, you actually saw a piece of paper taped to the inside that had a schematic diagram, so that if it did break down, you could refer to it and try to make repair possible. You don’t have that now, but you do have I Fix It guides and other people who demonstrate, oh yes, this is how you take apart your Xbox, and you can access your hard drive. And so I do that a lot. There’s a robust community of people who do that. And there are a lot of other people who fight to the point where they’ll even hack some stuff to make repair possible. I’m not sure if you’re aware that a video by Louis Rossmann -it’s also featured in Forbes – a German gentleman found a way to bypass some of the techniques that were only available through Apple. So he was able to make a repair cheaper by using a tool that he created. That’s on his YouTube channel. But I’m kind of rambling a little bit at this point. But yeah, just education has been probably the biggest point where we don’t see that in schools now. shop class. Maybe the robotics teams and the STEM classes might help a little bit there on the making side, but I think that’s a good step because I think before you make, and maybe even after you make, there’s a troubleshooting part. Then there’s also the maintenance part afterwards.

L: Yeah, it’s so interesting. I feel like I’m opening a lot of different mental tabs of what you’re saying. So what would be something that most people might not know about repair or maintenance?

V: I think people don’t really realize a lot of companies are engaging in anti-repair and anti-maintenance type practices. They noticed the design trend to go lighter and lighter and thinner and thinner. I think about that a lot, because a very long time ago, people put more value in weight, and heft. So when people would buy a landline telephone, a lot of them would actually figure out the weight and choose the heavier one. But now, things like smartphones will get measured in millimeters, in ounces or grams. But people don’t realize that it comes at a maintenance price. That includes the use of glue, and rather aggressive glue that requires a heat gun to use over your screen, if you want to start repairing it. And the manufacturers have also engaged in parts-pairing where something like if you had two iPhones, same model, same exact everything. And if you just switch the screens, both of them would spit a message back at you saying, “Yeah, this isn’t the original screen”. And some functions may not work. Because you use a different one. Even though it’s genuine Apple, it just came from a different phone. So I think a lot of people are not necessarily aware of practices that are not repair and maintenance friendly. I’m thinking about the screen most often, because that that part breaks the most often. But it’s not an easy process. At least not for somebody who only does it maybe once or a few times in a lifetime repair shopping, maybe but not a casual owner.

L: I’m curious to hear your thoughts… We recently had an event with one of our fellows (Mathew Lubari) that is also in the Repair Cafes’ world. And he had an event, “The Essence of Repair Culture” that was convening people in this context. One of the speakers mentioned that there are some concerns about liability issues of people bringing objects and how at some point that could present a risk to the people that were doing the repairs. Do you think that is something that could happen?

Caption: In the case of objects like this washer, safety is crucial, as water leakage could be dangerous.

V: Oh, yeah, I’m pretty sure that there’s a risk of injury of all sorts, so much so to the point where when we’re at the gallery in Brooklyn- we kind of made our gallery with people rather edgy, because we didn’t have liability insurance- We didn’t have anything to cover that. But we also did our best to manage expectations by saying “Yes, something could happen.” But we also had a very lengthy discussion about how to make things as safe as possible. I’m thinking about somebody who brought in a portable washer that needed a new hose. So you just wanted to figure out how to be sure the seal was tight, because if it leaked, that was really bad news and that has already happened. In a lot of the hackerspaces, there’s already that kind of liability in place. Everybody who comes in signs a waiver, you know, especially when they use these tools. Now I kind of remember joking about that at Maker Faire, I had to sign that too. So I waved this piece of paper and said “Yo, who needs the ‘I can’t sue anybody’ form?”. I knew how it worked, and I knew that they had to do it too to protect us. And sure, I have been burned too, literally by grabbing a soldering iron in the wrong place. And my friend told me to put your hand in the freezer, like really? Yeah. Okay. So liability waivers help. And yes, there is a risk.

L: Okay! Well, it sounds like you also try to make things safe.

V: Sometimes we have a joke, it came from some place called The Madagascar Institute. They don’t deal with Africa, but they have a running joke “ Safety third!”. It means if you want to make cool stuff, you have to take some chances!

L: Any final thoughts you would like to share today?

V: I’m still fixated on implementing the business continuity plan, and kind of get things back up and running, with bigger and better social media presence because we use Google workspace… We’ve been extorted to pay money from Google and we can’t convince them that we’re not a commercial venture, but they weren’t didn’t have it, so we my email is down on the Fixers Collective side, but we look forward to getting that momentum back up and running especially some of our host have gone away and moved from 14th street, and our Brooklyn venue shut down, so we are scouting for locations.