A Trip Down the Arroyo Seco – A Microcosm of Infrastructure, Nature, and Society Part I

– By Tonatiuh Rodriguez- Nikl

Introduction

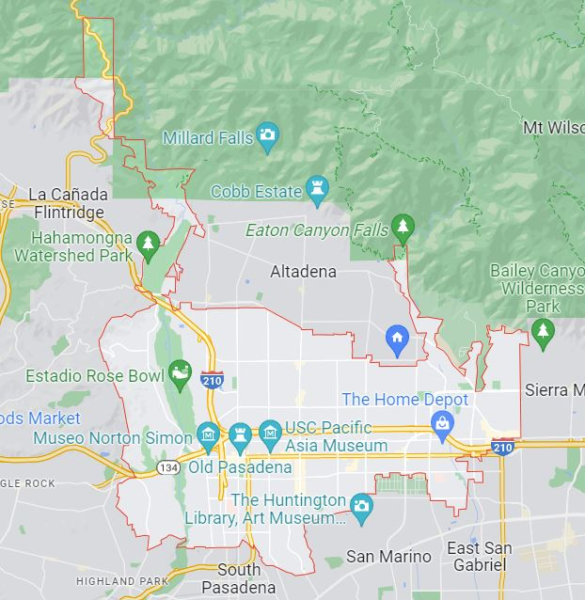

The Arroyo Seco (Dry Stream in Spanish) meanders down the San Gabriel mountains, into Pasadena, and later joins the Los Angeles River near Downtown. Over the course of two blog posts, we’ll take a trip down a roughly 20 km segment of the Arroyo, to see what it teaches us about nature, society, and infrastructure. This first part focuses on the relationship between nature and infrastructure.

As we travel down the Arroyo we’ll observe how the natural stream is gradually slowed by dams, removed for groundwater, and contained in concrete channels. Yes, this infrastructure responds to important and legitimate needs for drinking water and flood control. At the same time, it damages the natural habitat, it is ugly, and it leads us to forget our dependence on the natural world. At the end of this post I’ll reflect briefly on social attitudes that led us to desire and build such infrastructure as well as a possible alternative.

I made this trip on a mountain bike, starting with an hour and a half climb into the San Gabriel Mountains. That wasn’t the most direct route, but it afforded me a great view from the ridge above the Arroyo. We’ll start our journey together from that ridge.

Entering Urban Space

We start the trip in the San Gabriel Mountains along the northern edge of the Los Angeles Basin. The Arroyo is visible in the canyon below, having originated about 5 km further up the mountain. We descend along switchbacks, overgrown in a few places with poison oak. Out here, there are few signs of human presence, but soon enough, the Arroyo arrives at its first dam. It’s hard to imagine that this gentle, trickling stream would ever need to be restrained by massive concrete dams, but the flood risk is real. After the dam, signs of development become increasingly obvious: segments of an abandoned road, check dams, and pedestrian bridges. A drinking fountain next to ranger houses is the first sign of potable water (some of it coming from the Arroyo). We then reach a paved service road that takes us out of the mountains and into the Hahamonga Watershed.

Hahamonga Watershed Park

After its trip down the San Gabriel Mountains, the Arroyo Seco arrives at Hahamonga Watershed Park. The Park and surrounding areas, originally inhabited by the Tong-Va people, contain a frisbee golf course, trails, horse stables, developed picnic areas, and NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL). At the south end of the park lies Devil’s Gate Dam, the main flood control structure along the Arroyo. Along the east bank of the Arroyo are spreading basins, which roughly speaking are large, flat holes into which some of the Arroyo’s water is pumped. Managing this watershed involves a constant tension between different priorities, including flood protection, groundwater management, and fish and habitat conservation. We’ll see two examples in the following paragraphs.

The first example involves an argument over the need for new spreading basins. The city of Pasadena draws much of its water from an aquifer that spans across the Hahamonga watershed. This aquifer’s water level has been declining steadily since 1910. To help recharge the groundwater and to obtain credits to use its water, the city diverts water from the Arroyo to the spreading basins. However, this damages the river habitat and, some people argue, is unnecessary because the groundwater could be recharged adequately by a naturally flowing stream.

A second example starts in 2019 with a sediment removal project at Devil’s Gate Dam. Although the project entailed the removal of a large swath of riparian vegetation behind the dam and initially faced strong opposition from residents, local schools, and environmental activists, an effective public engagement process eventually gathered significant agreement, including support from the vocal Arroyo Seco Foundation and the local native plant nursery that provided most of the plants for the restoration.

After playing its role in these contentious battles involving residents, environmental activists, and various government agencies, the Arroyo emerges from Devil’s Gate Dam to continue towards the Los Angeles River.

The Rose Bowl

After being harnessed by Devil’s Gate Dam, the Arroyo Seco discharges in a controlled flow, crosses under its first freeway and is soon confined to an uninviting concrete channel, one of many flood-control channels in the Los Angeles basin. (These channels may be ugly, but they make for good chase scenes!) The channel passes through the Rose Bowl area, which has several walking paths, playgrounds, and sport facilities. Along this stretch, the Arroyo meanders unceremoniously through a golf course (watered with potable water) and past the iconic Rose Bowl stadium. The Arroyo has transitioned from a central feature in the mountains to a hidden urban gutter.

Conclusion

This journey down the Arroyo Seco points to a relationship between humans and nature based on control and certainty. The dams and the channels will undoubtedly stop the floods. The simple geometry of the concrete channel tames the natural stream and produces nice, predictable flow. Similarly, the spreading basins render it unnecessary to understand infiltration along the natural but complicated streambed. Control and certainty aren’t necessarily bad (after all, who would argue for impotence and uncertainty?) but they are bad if they are achieved at the cost of neglecting important considerations. This infrastructure is ugly, uninviting, damages the natural habitat, and invites us to deplete our water stores thoughtlessly while keeping lawns green in an arid climate; these and other similar considerations were ignored when the infrastructure was designed.

We like to think of our world in terms of “problems” that we can “solve” with technological artifacts. Coming from a problem-solution paradigm, the problem of insufficient water entering the aquifer is solved by building something to put more water in. The problem of floods is solved by building dams and channels to slow and control the water. This approach is intellectually easy and politically attractive (“Look, I solved your problem. Reelect me!”) but the very act of defining a problem in a large, complicated system like the Arroyo, reduces the scope of the relevant issues considerably, spawning secondary problems in the wake of the so-called solutions. Infrastructure tends to lock in these secondary problems because it is durable and expensive to replace.

How about instead, we reframe these issues as maintenance challenges? Let’s ask how we can maintain the interconnected systems that sustain us. Let’s view ourselves and our relationship to the rest of the world – the Earth and all its inhabitants – not through a lens of control but one of continuous cycles of understanding, adaptation, and monitoring with a sensitivity to the many physical and social influences involved as well as the wide range of human needs that are served.

Coming Next

Check out “A Trip Down the Arroyo Seco: A Microcosm of the Relationship between Technology, Nature, and Society Part II”. Here will continue our trip down the Arroyo, turning our attention to socioeconomic observations. The stark contrast we observe between the affluent and poor residents along the Arroyo’s banks will lead us to reflect on the ways that socioeconomic factors led to the channelization of the Arroyo almost a century ago.