A visit to the Tool Library at Greenpoint Library: repair economies, object lending, and new production paradigms in times of climate change

-By Lauren Dapena Fraiz

“The time has come for us to reimagine everything.” Grace Lee Boggs

It is well-known among library professionals that in our neoliberal world, it would be impossible to invent libraries now if they hadn’t existed since antiquity. Our economic systems are so intertwined with the interests of businesses that lending books to be free would simply not be allowed- it would go against all copyright, patents, and product protections that forefront profit over human benefit. Thus, libraries are truly an oasis of free and open knowledge and a bulwark against censorship, continually battling closure and budget cuts (such as Mayor Eric Adams’s infamous suspension of weekend service in 2024, revoked due to severe public backlash). Covering gaps in public services well beyond the lending of books, libraries in New York City offer a wide array of community resources, including tutoring for children, cooling centers during heat waves, and food security stations, among many others. The baseline of libraries are revolutionary and challenge overconsumption cultures, and when we think of libraries as a model, we can envision new systems for social change. What would our world look like, and how could our consumption/production chain change, if we relied more on institutional or collective lending models?

While the more immediate association is with that of a repository of books, the library model does not only revolve around this alone. A range of materials, including magazines, digital programs, and media, can be found in public libraries. We use the term “library” in a quite dynamic way. While libraries are often public institutions funded by taxes and, increasingly, philanthropy, they can also be affiliated with universities or cultural institutions. They also exist on a more informal scale, as community organizations, schools, or activists groups also host libraries. In the case of Tool Libraries, we will learn that their resourcing and governance vary depending on whether they are housed by a public institution, volunteer-run, or reliant on membership dues. Some are completely free to users (like the Tool Library at Greenpoint Library), others are more similar to coop models and may require a membership, and others operate as a business. For this blog post, I will focus more on the notion of object-lending, regardless of whether the model is funded publicly or privately. Jason Naumann of the National Tool Library Alliance describes tool libraries as

“ a growing resource worldwide, providing free or low-cost access to tools for repair, home improvement, construction, crafting, and gardening […]. As resource hubs, tool libraries support individuals and community-based organizations completing clean-up projects and small construction in disaster recovery efforts and emergency response, as well as everyday projects to improve neighborhoods, shared spaces, and homes”.

A Tool Library is similar to another popular object lending program that gained popularity in the mid-2010s: the “Library of Things”. This program operates in a similar way that a book-lending service does: patrons check out an item for a period of time, and return it in the same condition as it was loaned. The main idea is to borrow objects that we do not need to use often, don’t want or need to own, and/or that we would have trouble storing or preserving in the long term. For example, the company that first established Library of Things in the UK, inspired by the Tool Library of Toronto, includes eclectic objects such as sewing machines, trolleys, travel cribs, tents, extendable ladders, microphones, portable amps, carpet cleaners, ice-cream makers, and even a gazebo.

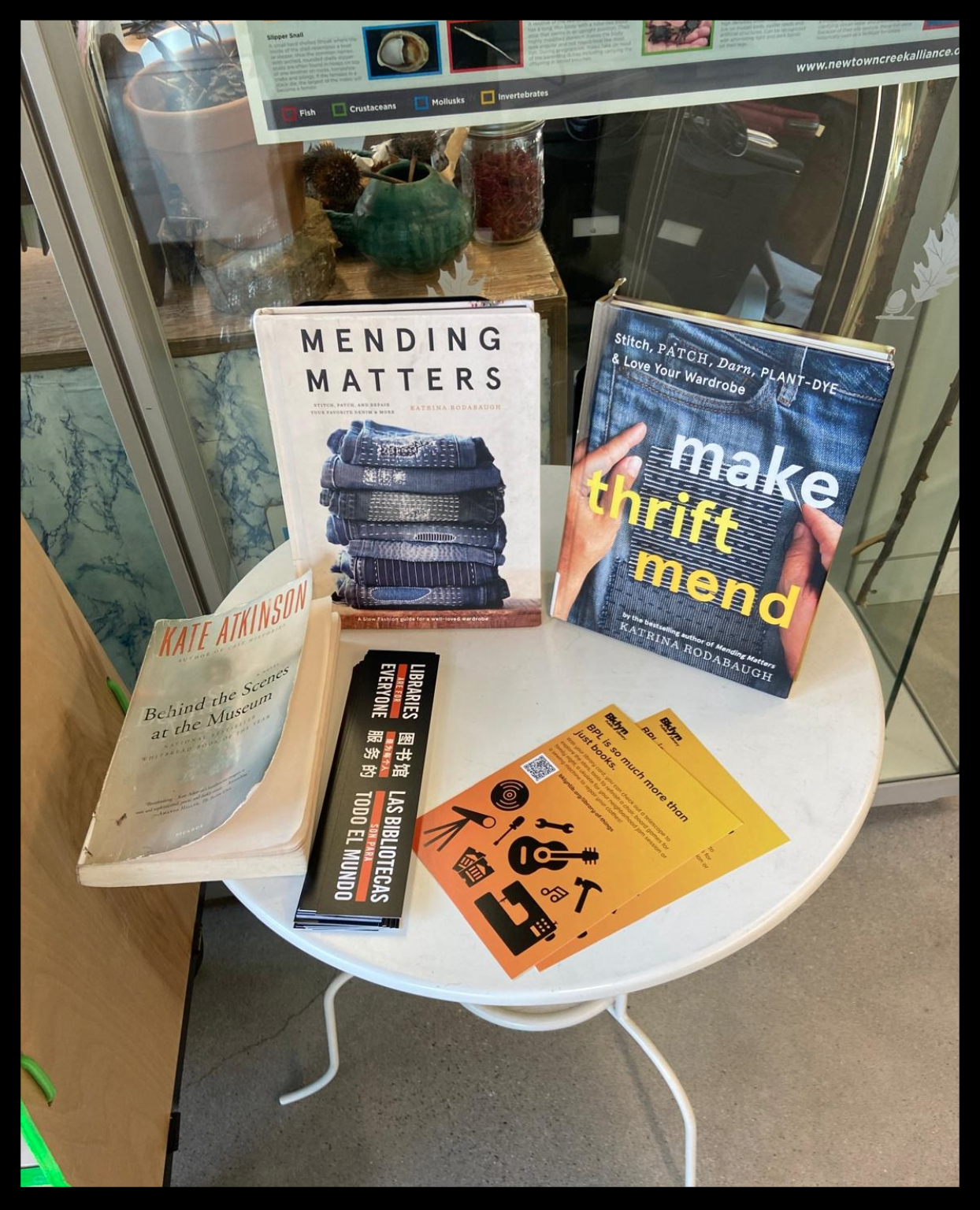

While the range of necessity for these items varies widely – needing to borrow an extendable ladder is likely to be more essential than borrowing an ice cream maker – we can all agree that it is practical to not purchase an object just because we need it once or twice, especially if the object may be expensive, or perhaps take lots of space to keep in tight living quarters. Many of us would no doubt have trouble figuring out where to wheel in and comfortably keep a large trolley in a small apartment. Especially in the case of free or low-cost lending programs, users gain access to new possibilities, even if they can’t afford expensive equipment. For example, a person curious about sewing might borrow a sewing machine for a set period from the Library of Things. This access provides enough time to learn the basics, complete some mending projects, and decide whether owning a sewing machine is necessary.

The convenience of borrowing objects for occasional use is clear, however, we still inhabit spaces that require repair, filled with possessions that break or wear out. Here is where the tool libraries step in as a powerful path for self-reliance. The ethos of efficiency in tool libraries, and in the larger scene of Repair Economies, can provide wider access to repair materials, potentially shifting our consumerist patterns. As many sustainability experts point out, western societies are hooked to constant shopping and widespread services such as Amazon, which makes it easier to buy things constantly, and more convenient and cheaper to replace materials rather than taking the time to fix things. It is not a stretch to say that this becomes a habit or even a compulsion. That is; if you don’t know how to fix things in the first place. As repair advocates point out, perhaps if people knew how much you can save by repairing your objects and the personal satisfaction doing so entails, they would be more interested in fixing more.

The Tool Library at Greenpoint Library: tools in the middle of an environmental disaster site

On a sunny September morning, I biked over to the Greenpoint Public Library, home of a local tool library, to meet with Acacia Thompson who works there as an Environmental Justice Coordinator and was responsible for launching the tool library. The building was completely remodeled and was unrecognizable from the 1970s Lindsay-box architecture in place the last time I visited about 7 years ago. In the fall of 2020, a quiet pandemic inauguration revealed a brand new state-of-the-art library branch, boasting an environmentally conscious design and also deemed an Environmental Education Center dedicated to climate advocacy and education.

The environmental approach of this library is no coincidence, as the renovation itself is a consequence of a legal settlement between the city of New York and fossil fuel multinational ExxonMobil. As Acacia contextualized, The Tool Library and other environmental programs in the Greenpoint Library exist as a response to the tragic history of Greenpoint as an urban site of pollution disasters. The Greenpoint Oil Spill on Newtown Creek from ExxonMobil is perhaps the most dramatic one, as it is one of the most damaging and largest oil spills recorded in US history. This ligation case against ExxonMobil, filed in 2015, was brought on by community stakeholders and prosecuted by the NY State Attorney Generals office. Although government authorities only officially admitted to the environmental damage in 1978, evidence supports that leakage has been ongoing since decades before, and for years, Newton Creek remained one of the country’s most toxic waterways. Other notable events include the infamous abandoned NuHart Plastics factory on Dupont Street, which left a legacy of soil contaminated with phthalates and the carcinogen TCE. Despite this history and in opposition from neighborhood community boards, it is now the site of a brand new luxury housing development.

Standing amidst this complicated history, the Greenpoint Library is an energy-efficient infrastructure that houses a rooftop garden with lush vegetation that includes berries, lavender, mint, and other types of herbs and vegetables, a pollination station, solar panels, and a rainwater harvesting system.

The Tool Library at Greenpoint Library is New York City’s first tool library within a public library, is a unique, free resource, drawing members from all boroughs. While tool libraries may sound like an immediately appealing idea, Acacia highlighted that one reason they’re not more widely launched is the issue of liability. It makes sense that many administrators would consider loaning tools to the general public is just too risky, and not worth the headache, particularly when the public is unaware of the existence of tool libraries and thus not demanding it. Tool Libraries therefore only exist if there is a strong repair advocate or even a hobbyist with a “maintenance mindset”, such as Acacia, who before becoming library staff was a film set designer and also a fixer outside of her work.

It takes care and dedication to launch a tool library, frequently relying on the advocacy of a deeply committed individual who considers the library “a pet project” of sorts. In the context of a public library, you need to establish a brand-new lending infrastructure from scratch that still manages to comply with the library rules and be willing to provide oversight so that the program runs smoothly. To make the library a reality, it was fundamental to highlight the communal benefits of the program. This allowed the project to move forward provided certain rules and guardrails were in place (“no chainsaws!”).

To address liability issues, the the Tool Library requires that borrowers be patron of the Brooklyn Public Library and sign a legal waiver in which both parties agree the library is not liable for anyone getting hurt with the tool. This raises another consideration: beyond access to tools, how do users gain the education, skills, and knowledge on how to use them? When we face a broken object or some damage in our homes, we are often not required or expected to have these skills, particularly if we live in Global North and urban environments, and are busy keeping up with other aspects of the hustle and bustle of city life. While certain repair skills absolutely require highly skilled professionals such as plumbers, electricians, engineers, mechanics, or other types of repair-related workers, for more simple repair tasks people often outsource repair rather than learn how to do it. Other times, they opt for another quick solution: replace and buy new.

In this sense, an educational component is critical to assume the responsibility of using tools, so here they point patrons to educational videos, often featuring women instructors which Acacia deliberately chose. The decision on what tools to catalog is based on a community needs assessment filled out by library patrons and community members. Aside from shop tools that were too large to be effectively loaned, Acacia found that “Mostly people wanted different kinds of power tools that they would only use infrequently, different kinds of saw horses, even just regular types of hand tools. They were interested in gardening tools”.

Taking on repair tasks makes one more knowledgeable about the value, time, and attention that it takes to adequately maintain and care for our objects and infrastructures. Acacia points out that instead of outsourcing their labor, patrons can

“Take care and repair their own things in their home. They can think about the things that they own, about taking care of them, instead of pitching them and throwing them away and then just buying something new […] Having tools and being able to show them, this is how you can, refinish that table that you wanted to get rid of”

This circularity spreads on to other initiatives too, as lending, swapping, and exchange groups grow more commonplace. The next step for the Tool Library at Greenpoint Library is to host a series on tool repair and usage. Transferring these activities to an educational setting fosters community connectivity and collaboration and also bridges the generational knowledge gap in repairing both traditional and modern electronic technologies. As many repairers, menders, fixers, and crafters know, it is through this sense of community of practice that individuals can build their knowledge, and also extend their skills to become better and more solidary citizens for the benefit of the community at large.

A glimpse into the larger Tool Library and Repair Economy movement

As mentioned, tool libraries vary in their structure, model, and governance framework, but what is clear is that they are part of a vibrant movement promoting repair and responsible stewardship. In a recent Maintainers Meet Up, Leanna Frick of the National Tool Library Alliance, and one of the leaders of Station North Tool Library, talked about their membership-based tool library in Baltimore which is run by the community and independently financed. It provides classes for people on home care, metal, and woodwork, and has an impressive reach: over 1,308 active borrowing members and over 150,846 loans since its inception in 2013. The Flatbush Tool Library by Flatbush Mixtape, a collective situated in “one of the largest and most diverse Afro-Caribbean communities in the region”, created a fully free tool library that is open twice a week as part of their larger restorative and transformative justice mission. Their website states a sentiment full of common sense that captures its unquestionable public benefit: “It doesn’t make sense for 100 people on the same block to collectively each buy a drill that will sit and gather dust between uses”.

The Repair Economy Summit 2024 exemplifies the larger, thriving repair economy movement of which tool libraries are a part. This gathering in December 2025 – led by Kami Bruner of Repair x Reuse Washington – brought together policy professionals, scholars, community-based makers, fixers, reuse advocates, buy-nothing groups, and repair cafe leaders. The summit showed just how creative and enthusiastic repair communities are and how creative the approach is for tool lending specifically. For example, Dante Garcia, of Community Gearbox, puts forth a participatory and decentralized tool inventory that does not require a physical space, which can be a way to address problems related to the high costs of rent or the inability to adequately staff these spaces. Tool libraries can even prove their worth in a climate crisis: the Asheville Tool Library, was instrumental in filling a service gap when Hurricane Helene left neighbors stranded. The tool library – serving over 30% farmers and rural, disbursed neighbors- was able to mobilize resources and take on disaster recovery work in partnership with a local anarchist book store and regional partners WNC Repair Cafe. It is fair to say tool libraries, as well as practices of repair and maintenance, offer important pathways toward new, circular economic models, as explored in the Field Notes on Repair from the November 2024 issue of Places Journal.

The Repair Economy and Tool Libraries are central to a broader dialogue about how we can educate on tool use and facilitate object repair, especially in the face of corporate interests that oppose these practices. As advocates of repair point out, repair skills have become increasingly siloed as consumption trends -discard ability, single-use, shortened product lifecycle- have appeared over the past decades. While professional repair has existed forever, companies increasingly restrict consumer access to repair knowledge and parts, making consumers fully dependent on the markets. Campaigns like PIRG’s Right to Repair, led by Maintainers Steering Committee member Nathan Proctor, have successfully challenged corporations such as Apple and John Deere for their poor track records of anti-repair practices, including proprietary designs, glued components rather than screwed in, and the lack of clear (or any) repair manuals. These companies often rely on planned obsolescence, and under the guise of patent protection, keep repair knowledge exclusive within their private services (e.g., Apple Genius technicians). This forces consumers to buy new products instead of repairing old ones. The efforts of advocacy groups have been critical in pushing regulations that obligate corporations to adopt more repair-friendly practices.

To conclude, tool libraries are still in their early stages, and face lots of unknowns regarding how to be administered in the long term. There are complexities in dealing with property damage, tool care, unreturned items, funding, and overall day-to-day oversight. For anyone interested in the tool library movement, I recommend joining the International Tool Library Google Group, a dynamic group full of experts in different corners of the country and world that exchange best practices, information on waivers, membership or governance models, best tools to buy, and more. Other resources worth checking out, if you are interested in starting your own sharing hub in your community, check out Shareable’s Library of Things Co-Lab or Tool Kit. Despite some growing pains, we are witnessing progress, growth, and opportunities for fine-tuning. It is our responsibility to create new institutions that can save our Earth, and repairing economies can be a starting point to embrace a new way of thinking. comprehensive guide to starting (and growing) a sharing hub in your community.

Please feel free to reach out if you have any questions or thoughts on this article by emailing [email protected] .